180-Day Exclusivity and Authorized Generics: Legal Pitfalls and Market Impact

Nov, 20 2025

Nov, 20 2025

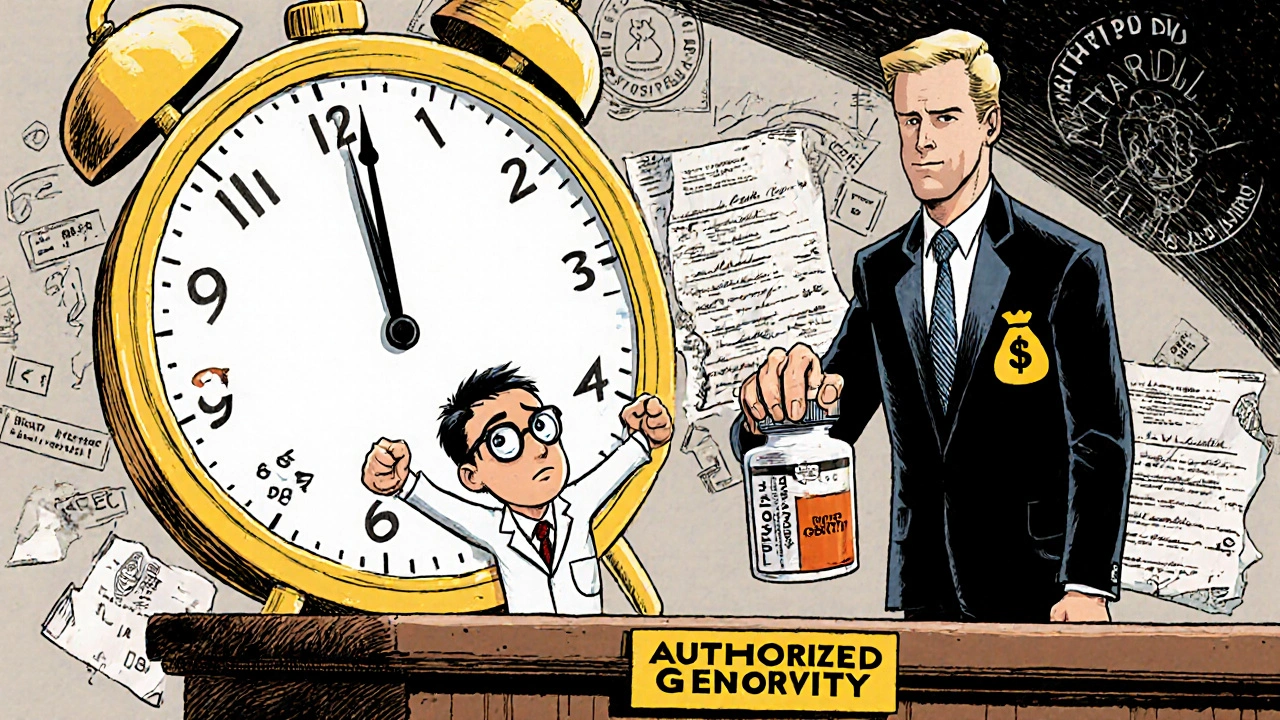

When a generic drug company wins the right to be the first to sell a cheaper version of a brand-name drug, it’s supposed to be a big win. For 180 days, no other generic can enter the market. That’s the promise of the 180-day exclusivity rule under the Hatch-Waxman Act. But here’s the catch: the brand-name company can still launch its own version of the generic-same pill, same factory, same active ingredient-just without the brand name. This is called an authorized generic. And when it happens, the first generic’s market share plummets. What was meant to be a reward for challenging a patent turns into a race against the very company that made the original drug.

How the 180-Day Exclusivity Rule Was Supposed to Work

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 was designed to fix a broken system. Before it, brand-name drugs had years of monopoly power. Generic companies couldn’t even start testing their versions until the patent expired. That meant patients waited years for cheaper options. The law changed that. It let generic manufacturers file an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) while the brand-name patent was still active-so long as they claimed the patent was invalid or not infringed. That’s called a Paragraph IV certification.If they won in court or forced a settlement, they got 180 days of exclusive sales. No other generic could get FDA approval during that time. The idea was simple: reward the company that took the legal risk. That first generic could capture up to 80% of the market, selling at a steep discount to the brand. In some cases, that meant hundreds of millions in revenue.

But the law never said the brand-name company couldn’t join the party.

Authorized Generics: The Legal Loophole

An authorized generic isn’t a copy. It’s the exact same drug. Same manufacturer. Same factory. Same packaging-except the brand name is gone. The brand-name company licenses its own drug to a distributor, puts it in a plain bottle, and sells it at generic prices. Legally? Totally allowed. The FDA doesn’t require any extra approval. The drug is already on the market. All they do is change the label.And they can do it the moment the first generic launches. No waiting. No rules against it. That’s the problem.

Between 2005 and 2015, about 60% of the time a generic company won 180-day exclusivity, the brand-name company launched an authorized generic within days. When that happened, the first generic’s market share dropped from 80% to around 50%. Revenue? Cut by 30-50%. In one case, Teva Pharmaceuticals estimated it lost $287 million because Eli Lilly launched an authorized version of Humalog right as Teva’s exclusivity started.

This isn’t just bad luck. It’s strategy. Brand-name companies know the value of that 180-day window. By launching their own generic, they split the market. They keep some of the profits. They prevent the first generic from building momentum. And they make it harder for other generics to enter later.

Why This Matters for Generic Companies

Challenging a patent isn’t cheap. It costs between $2 million and $5 million in legal fees alone. For a small generic company, that’s more than their annual budget. They take that risk because they believe the 180-day exclusivity will pay it back. But when an authorized generic shows up, that payoff vanishes.According to Drug Patent Watch, 78% of first generic applicants now negotiate with brand-name companies to delay or block authorized generic launches as part of patent settlement deals. Some even pay the brand-name company to stay out of the generic market. That’s called a “pay-for-delay” agreement-and it’s under heavy scrutiny by the FTC.

Smaller companies are dropping out. Why risk $3 million in legal fees if the brand can just flood the market with its own version? The incentive is broken. The FDA’s own data shows that 28% of first applicants between 2018 and 2022 lost part or all of their exclusivity because they messed up the timing-filing too early, shipping too late, or failing to prove they were actually selling the drug. Add an authorized generic on top of that, and the odds of success shrink even further.

The Legal Gray Zones

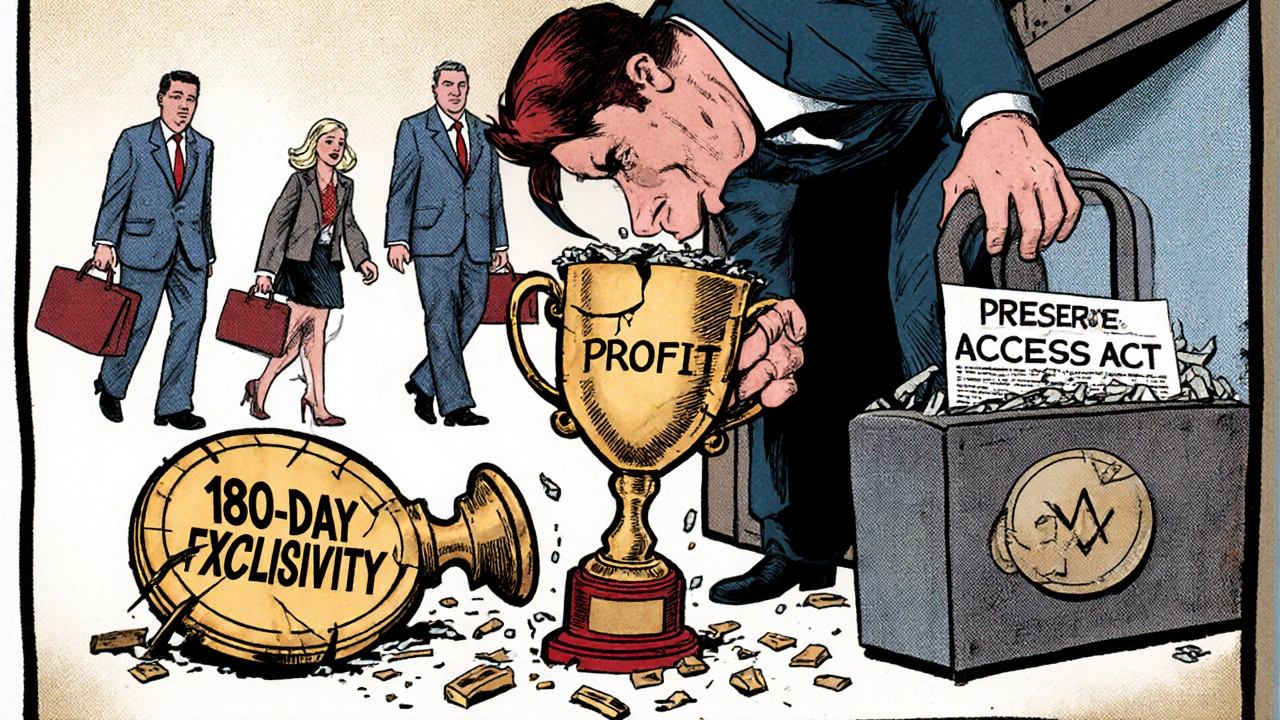

There’s no law saying brand-name companies can’t launch authorized generics during exclusivity. But that doesn’t mean it’s uncontroversial. The Federal Trade Commission has filed 15 antitrust lawsuits since 2010 accusing brand-name companies of using authorized generics to delay competition. In some cases, they argue the brand and the authorized generic distributor are secretly working together to keep prices high.Meanwhile, Congress has tried to fix this. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act has been introduced in every session since 2009. It would ban brand-name companies from selling authorized generics during the 180-day window. The FDA’s Commissioner Robert Califf said in 2023 that the agency supports this change. The FTC agrees, estimating that blocking authorized generics would boost first-generic revenues by 35% on average.

But the pharmaceutical industry pushes back. PhRMA argues authorized generics lower prices faster. A 2021 RAND Corporation study found that when an authorized generic competes with the first generic, drug prices drop 15-25% more than if only one generic is on the market. That’s true. But it’s also true that the brand-name company is still the one collecting most of that revenue. The first generic gets squeezed out. The patient saves money-but the real winner is the original manufacturer.

What’s Changing Now?

The landscape is shifting. Generic companies are getting smarter. They’re building legal teams focused solely on exclusivity timing. They’re tracking FDA approvals down to the hour. They’re hiring consultants to make sure their first shipment happens exactly when the clock starts-because if they’re even a day late, they lose the whole 180 days.Big players like Teva and Mylan have entire departments dedicated to this. But for small companies? It’s nearly impossible. The cost of getting it right-legal, regulatory, logistical-can hit $1 million. That’s why many are walking away from Paragraph IV challenges entirely.

And the numbers show it. In 2000, it took an average of 28 months for multiple generics to enter the market after a brand-name drug lost exclusivity. By 2022, that time dropped to just 9 months. Why? Because the first generic rarely gets to enjoy its monopoly. Authorized generics, followed quickly by other generics, flood in. The market collapses fast.

Who Wins? Who Loses?

Patients get lower prices sooner. That’s good. But the system is rigged. The company that took the biggest risk-the one that spent millions challenging a patent-gets punished. The brand-name company, which didn’t have to do anything but wait, walks away with most of the profits.The Hatch-Waxman Act was meant to speed up access to affordable drugs. It did that. Since 1984, it’s saved the U.S. healthcare system over $2.2 trillion. But the 180-day exclusivity rule is no longer delivering on its promise. It’s become a tool for brand-name companies to control the market, not a reward for challengers.

The real question isn’t whether authorized generics are legal. They are. The question is whether the law should change to stop them during the exclusivity window. If Congress doesn’t act, the incentive to challenge patents will keep fading. And that means fewer generics overall. That’s not innovation. That’s stagnation.

What’s Next for Generic Manufacturers?

If you’re a generic company considering a Paragraph IV challenge, here’s what you need to do:- Calculate the risk of an authorized generic launch before you file. Ask: Has the brand done this before with similar drugs?

- Negotiate a deal. Many companies now include clauses in patent settlements that block authorized generic entry for 90-120 days.

- Build a cross-functional team: legal, regulatory, and commercial all working together. Missing one step can cost you the exclusivity.

- Track FDA timelines obsessively. The 180-day clock starts the moment you ship the first box. Not when you get approval. Not when you announce it. When the drugs leave the warehouse.

- Don’t assume you’ll get the full 180 days. Plan for 50% of that. That’s what most companies actually get.

The game has changed. The rules haven’t. Until Congress fixes the loophole, the first generic isn’t the winner. The brand-name company is.

Can a brand-name company legally launch an authorized generic during the 180-day exclusivity period?

Yes. There is no law prohibiting it. Authorized generics are simply the brand-name drug sold under a different label. The FDA allows them without additional approval, and they can be launched at any time-even the same day the first generic enters the market. This is a legal loophole built into the Hatch-Waxman Act.

How does an authorized generic affect the first generic’s market share?

When an authorized generic enters the market during the 180-day exclusivity period, the first generic’s market share typically drops from around 80% to 50%. This cuts potential revenue by 30-50%. In some cases, the brand-name company captures more of the sales than the first generic does.

Why don’t generic companies just wait for the exclusivity period to end before launching?

They can’t. The 180-day exclusivity is only valuable if they’re the first to market. If they wait, another generic can file and beat them to the punch. The whole point of the exclusivity is to reward the first challenger. Waiting defeats the purpose.

What percentage of 180-day exclusivity cases involve authorized generics?

Between 2005 and 2015, FDA data shows that authorized generics were launched in about 60% of cases where 180-day exclusivity was granted. More recent data from Drug Patent Watch (2022) indicates that nearly 80% of first generic applicants now negotiate with brand-name companies to delay or prevent authorized generic entry.

Is there any legislation to stop authorized generics during exclusivity?

Yes. The Preserve Access to Affordable Generics and Biosimilars Act has been reintroduced in Congress multiple times since 2009. It would ban brand-name manufacturers from selling authorized generics during the 180-day exclusivity window. The FDA and FTC support this change, but as of 2025, it has not passed.

How much does it cost to challenge a drug patent?

Challenging a single patent through a Paragraph IV certification typically costs between $2 million and $5 million in legal fees. For complex cases involving multiple patents, costs can exceed $7 million. This is why many small generic companies avoid these challenges unless they have strong financial backing or settlement deals in place.

Ibrahim Yakubu

November 22, 2025 AT 04:34This is the most blatant corporate theft I've ever seen in pharma. The brand-name companies didn't invent the generic, didn't risk the lawsuits, didn't spend millions challenging patents - and yet they get to swoop in like vultures and steal the reward. It's not capitalism. It's legalized robbery with a FDA stamp on it.

Brooke Evers

November 24, 2025 AT 03:56I just want to say how heartbreaking this is for the small generic manufacturers. I know people who work at these companies - they’re not greedy, they’re not CEOs in suits. They’re scientists, pharmacists, logistics coordinators who believe in affordable medicine. And then the big players just flip a switch and crush them. It’s not just unfair - it’s soul-crushing. We need to remember who’s really paying the price here: not the shareholders, but the people trying to make healthcare work.

Chris Park

November 26, 2025 AT 03:17Let’s be honest - this isn’t a loophole. It’s a coordinated cartel. The FDA, the FTC, the big pharma lobbyists - they’re all in on it. You think the ‘authorized generic’ is just a label change? No. It’s a pre-negotiated collusion. The brand company owns the distributor. The distributor is a shell. The patent settlement? A front. The 180-day exclusivity? A joke. They’ve been doing this since the 90s. Congress won’t touch it because they’re funded by the same PACs. The system is rigged from the top down. Wake up.

Saketh Sai Rachapudi

November 27, 2025 AT 13:54USA always think they own the world. In India we make generics for the whole planet and no one even talks about it. You guys have patent lawyers and courts and all this drama but we just make the medicine and ship it. You think your system is fair? Ha. You're the ones who blocked Indian generics for 20 years. Now you cry because your pharma giants got outsmarted? Grow up.

joanne humphreys

November 27, 2025 AT 22:58I’ve read through this entire post twice because it’s so important, and I keep thinking about how many people don’t understand this. The real tragedy isn’t that the first generic loses money - it’s that this discourages future challengers. If no one dares to challenge patents anymore, we stop getting new generics. And that means prices stay high longer. It’s a slow erosion of access. We need to fix this not because it’s unfair to companies - but because it’s unfair to patients who can’t afford insulin, epinephrine, or even antibiotics.

Nigel ntini

November 29, 2025 AT 11:12There’s a quiet heroism in these small generic companies. They’re not flashy. No IPOs. No TED Talks. Just people working late nights to get a pill out the door on time. And then the big guys show up with their own version - same factory, same chemist, same bottle - and suddenly the underdog is irrelevant. We need to celebrate the challengers, not just the corporations. Maybe if we stopped treating this like a business game and started treating it like a public health crisis, we’d see real change.

Priya Ranjan

December 1, 2025 AT 09:44Anyone who still believes in the American healthcare system is naive. This isn’t a loophole - it’s a feature. The whole system is designed to enrich shareholders while pretending to help patients. The first generic isn’t being punished - they’re being eliminated. And the FDA? They’re just the paperwork machine. If you think Congress will fix this, you’ve never watched a committee hearing. This is capitalism at its most cynical. And we’re all complicit by paying the bills.

Gwyneth Agnes

December 3, 2025 AT 01:51Authorized generics are legal. That’s it. No drama needed.

Ashish Vazirani

December 4, 2025 AT 06:19Oh, so now it’s a ‘loophole’? Let me tell you something - the entire U.S. pharmaceutical system is one giant loophole wrapped in a patent lawsuit and sold with a smile! The brand companies didn’t just ‘launch’ an authorized generic - they orchestrated a corporate assassination! The first generic? A sacrificial lamb on the altar of profit. And don’t even get me started on the lobbyists who write the laws while sipping champagne in D.C.! This isn’t capitalism - it’s a Shakespearean tragedy written by Goldman Sachs!

Mansi Bansal

December 6, 2025 AT 02:44It is with profound regret that I must observe the systemic disintegration of equitable market dynamics within the pharmaceutical domain. The authorized generic mechanism, while technically compliant with statutory provisions, constitutes a de facto anticompetitive stratagem that subverts the foundational ethos of the Hatch-Waxman Act. The economic disincentives thus imposed upon first-filer generic manufacturers are not merely regressive - they are structurally malign, precipitating a chilling effect upon innovation and market entry. Legislative intervention is not merely advisable; it is an ethical imperative.

Kay Jolie

December 6, 2025 AT 20:16Let’s talk about the structural arbitrage here - brand-name companies are essentially leveraging regulatory capture to extract value from a system designed to disrupt their monopoly. The authorized generic isn’t a product - it’s a strategic weaponized compliance tool. It’s a regulatory hack that turns the incentive structure on its head. And the worst part? The FDA’s hands are tied because the law doesn’t define ‘market entry’ in a way that protects the challenger. We need a new taxonomy: not just ‘generic’ and ‘brand,’ but ‘challenger-generic’ and ‘corporate-generic.’

pallavi khushwani

December 8, 2025 AT 15:21I think about this like a race. The first runner trains for years, risks everything, crosses the line - and just as they’re celebrating, someone hands them a towel and says, ‘Here’s your prize… but also, here’s your competitor with the exact same shoes.’ That’s what this is. It’s not about who makes the most money. It’s about who gets to be rewarded for taking the risk. And right now? The system rewards the people who did nothing.

Dan Cole

December 9, 2025 AT 22:51This is the perfect case study in how legal systems become instruments of power, not justice. The Hatch-Waxman Act was written by lawyers who understood incentives - but they never accounted for human greed. The 180-day exclusivity was meant to be a carrot. Instead, it became a mirror - reflecting the true nature of the pharmaceutical industry: not innovation-driven, but litigation-driven. The real tragedy isn’t the authorized generic - it’s that we’ve normalized this. We accept that the system is rigged because it’s ‘legal.’ But legality doesn’t equal morality. And we’re all paying for that delusion.

Billy Schimmel

December 10, 2025 AT 13:29So the brand company just says ‘hey, we’re gonna sell our own generic’ and suddenly the guy who spent $4 million and 5 years in court is out of a job? Wow. What a brilliant business model. I’m sure the shareholders are thrilled. Meanwhile, the patient still pays more than they should. And the real hero? The guy who got screwed. Good job, America.