Atrial Fibrillation During Pregnancy: Risks, Symptoms & Management

Oct, 4 2025

Oct, 4 2025

Atrial Fibrillation Risk Calculator

About This Tool

This calculator helps estimate risk factors associated with atrial fibrillation during pregnancy. It considers age, medical history, and symptoms to provide personalized risk insights.

Important Note

This tool provides educational guidance only. Always consult with your healthcare provider for accurate diagnosis and treatment recommendations.

Key Takeaways

- Atrial fibrillation (AFib) occurs in about 1 in 1,000 pregnancies and raises the chance of stroke and heart failure for the mother.

- Uncontrolled AFib can cause fetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and low birth weight.

- Rate‑control drugs (beta‑blockers, calcium‑channel blockers) are first‑line; rhythm‑control (cardioversion, ablation) is reserved for severe cases.

- Anticoagulation with low‑molecular‑weight heparin (LMWH) is recommended throughout pregnancy; warfarin and DOACs are avoided.

- Close multidisciplinary follow‑up-including obstetrics, cardiology, and anesthesiology-is essential from diagnosis to postpartum.

Understanding Atrial Fibrillation in Pregnancy

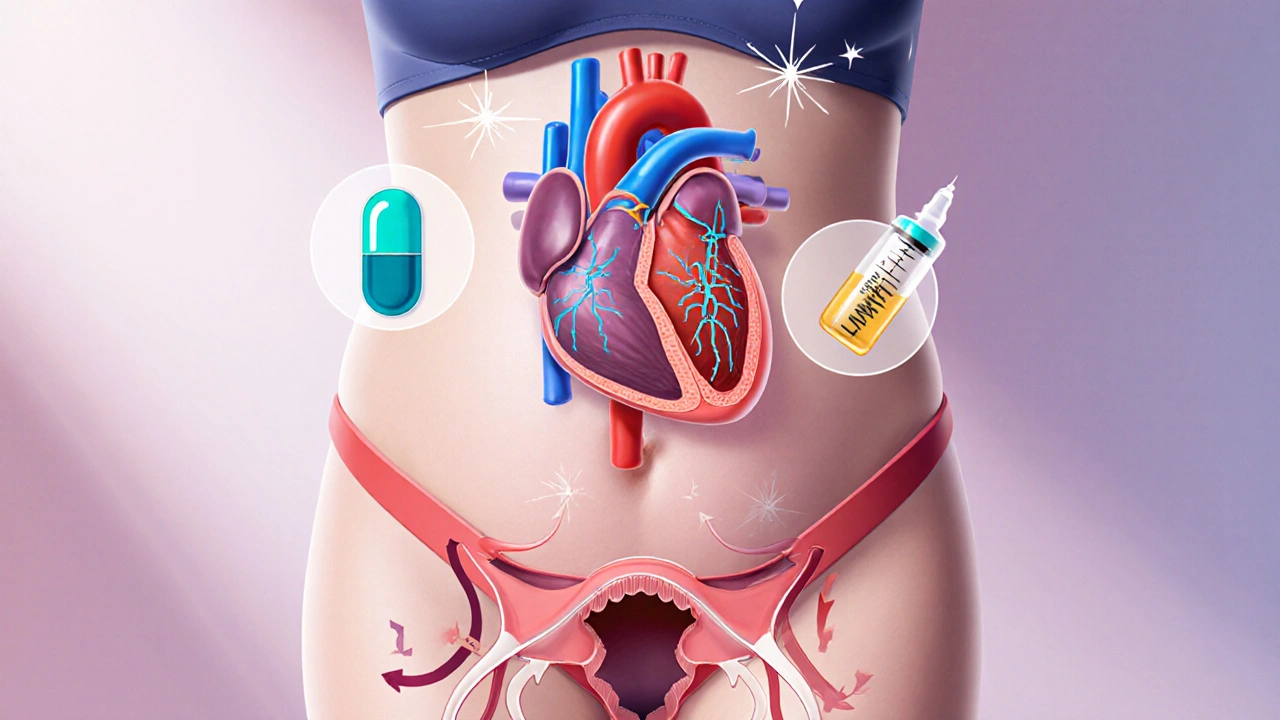

When we talk about Atrial Fibrillation is an irregular, often rapid heart rhythm that originates in the upper chambers of the heart (atria). In a pregnant woman, the heart already works harder-blood volume rises 40‑50%, cardiac output climbs 30‑50%, and hormone shifts increase excitability. Those physiologic changes can turn a borderline rhythm into full‑blown AFib.

Pregnancy is the state of carrying a developing embryo or fetus inside the uterus, typically lasting about 40 weeks. While most pregnancies are uncomplicated, underlying heart disease or new‑onset AFib adds a layer of risk that requires careful monitoring.

How Common Is AFib During Pregnancy?

Large registries from the United States and Europe estimate an incidence of roughly 0.1% (1 in 1,000) among all pregnancies. The odds rise to 1‑2% in women with pre‑existing structural heart disease, hypertension, or obesity. Age matters too-women over 35 have a noticeably higher risk, reflecting the general population trend.

Maternal Risks: What Can Happen to Mom?

AFib isn’t just an uncomfortable flutter; it can have serious downstream effects:

- Stroke: Irregular atrial contraction can let clots form and travel to the brain. Pregnant women have a hypercoagulable state, so the baseline stroke risk is already higher.

- Heart Failure: Rapid rates (often >120bpm) reduce filling time, leading to reduced output and, in severe cases, pulmonary edema.

- Maternal Mortality: Though rare, uncontrolled AFib combined with other comorbidities can be fatal.

Data from the 2023 AHA/ACC Pregnancy Registry show that women with AFib have a 4‑fold increase in ICU admission compared with uncomplicated pregnancies.

Fetal Risks: How the Baby Is Affected

When the mother’s circulation is unstable, the placenta can suffer. The main fetal concerns are:

- Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) due to reduced uteroplacental blood flow.

- Preterm labor triggered by maternal stress or medication side‑effects.

- Low birth weight and occasional NICU admission.

Importantly, the arrhythmia itself does not cross the placenta, but the treatments and maternal hemodynamics do.

Diagnosing AFib in a Pregnant Patient

Symptoms often overlap with normal pregnancy: palpitations, shortness of breath, and fatigue. However, a persistent irregular pulse or an ECG showing absent P‑waves and irregular R‑R intervals confirms AFib. A 12‑lead ECG is safe in pregnancy; radiation is not a concern. If the rhythm is intermittent, a Holter monitor or event recorder can be used.

Management Overview: Rate vs. Rhythm Control

Two strategies dominate:

- Rate Control: Keep the heart rate below 100bpm at rest. Beta‑blockers (e.g., metoprolol) are the go‑to drugs because they are well‑studied in pregnancy. Non‑dihydropyridine calcium‑channel blockers (verapamil, diltiazem) are alternatives if beta‑blockers cause severe bradycardia or hypotension.

- Rhythm Control: Try to restore normal sinus rhythm. Electrical cardioversion is safe after the first trimester, while anti‑arrhythmic drugs (e.g., flecainide) are generally avoided due to limited safety data.

The choice hinges on symptom severity, duration of AFib, and comorbidities.

Anticoagulation: Keeping Clots at Bay

Pregnancy is a hyper‑coagulable state, so anticoagulation is a cornerstone of therapy. The hierarchy is clear:

- Low‑Molecular‑Weight Heparin (LMWH) is the first‑line agent. It does not cross the placenta and has a predictable dose‑response.

- Unfractionated Heparin (UFH) may be used during labor when rapid reversal is needed.

- Warfarin and Direct Oral Anticoagulants (DOACs) are contraindicated because they cross the placenta and increase fetal bleeding risk.

Target anti‑Xa levels for therapeutic LMWH in pregnancy are 0.6‑1.0IU/mL (peak, 4hours post‑dose). Dose adjustments are required as weight changes.

Medication Safety Table

| Medication | Placental Transfer | Trimester Safety | Typical Dose (Pregnant) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metoprolol | Low | 1st‑3rd (monitor fetal growth) | 25‑100mg BID |

| Verapamil | d>Low2nd‑3rd (avoid high doses) | 80‑120mg TID | |

| LMWH (Enoxaparin) | None | All trimesters | 1mg/kg SC q12h |

| UFH | None | All trimesters (preferred intrapartum) | 5000U SC q8‑12h |

| Warfarin | High | Contraindicated (esp. 1st trimester) | N/A |

| DOACs (e.g., Apixaban) | High | Contraindicated | N/A |

Procedural Options When Medication Isn’t Enough

Electrical Cardioversion is a controlled, synchronized shock to the heart that restores normal rhythm. In pregnancy, it’s considered safe after 12 weeks gestation because fetal exposure to the brief electrical field is negligible. Fetal monitoring before and after the procedure is recommended.

Catheter Ablation is a minimally invasive technique that destroys the tissue triggering arrhythmia. It’s usually postponed until postpartum unless the mother faces life‑threatening tachycardia unresponsive to drugs. If absolutely necessary, a zero‑fluoroscopy approach using intracardiac echocardiography can limit radiation.

Delivery Planning and Postpartum Care

Women with AFib should deliver in a tertiary center with cardiology backup. Mode of delivery (vaginal vs. C‑section) is dictated by obstetric indications, not the arrhythmia itself.

During labor, a continuous ECG strip is useful. LMWH is stopped 12hours before induction or C‑section, and UFH is switched on if the estimated blood loss is high. After delivery, anticoagulation transitions back to warfarin (if long‑term) or a DOAC (once breastfeeding considerations are addressed).

Post‑partum AFib can persist or recur. Close follow‑up for at least 6months is advised, with repeat echocardiography to assess structural changes that may have developed during pregnancy.

Practical Checklist for Clinicians and Patients

- Obtain baseline ECG and echocardiogram at diagnosis.

- Start rate‑control beta‑blocker (metoprolol) unless contraindicated.

- Initiate therapeutic LMWH; adjust dose by anti‑Xa levels.

- Arrange multidisciplinary team: obstetrician, cardiologist, anesthesiologist, hematologist.

- Plan for continuous cardiac monitoring during labor.

- Switch to UFH 12h before delivery; resume LMWH 24h postpartum if bleeding is controlled.

- Schedule a 6‑week postpartum cardiac review to decide on long‑term rhythm strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can AFib cause miscarriage?

AFib itself does not directly cause miscarriage, but severe uncontrolled arrhythmia can lead to reduced uteroplacental perfusion, which may increase the risk of early pregnancy loss. Prompt rate control and anticoagulation reduce that risk.

Is it safe to breastfeed while on LMWH?

Yes. LMWH is a large molecule that does not pass into breast milk in clinically meaningful amounts, making it compatible with exclusive breastfeeding.

What symptoms should prompt an emergency visit?

Sudden severe palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, fainting, or signs of stroke (numbness, facial droop, speech difficulty) require immediate medical attention.

Can a pregnant woman take a DOAC if she has a mechanical heart valve?

No. DOACs are contraindicated in pregnancy, especially with mechanical valves, because they cross the placenta and increase fetal bleeding risk. Warfarin is also avoided in the first trimester, so LMWH bridging is the recommended approach.

Is a home blood pressure monitor useful for AFib patients?

Yes. Monitoring blood pressure helps gauge the impact of beta‑blockers and ensures that hypotension isn’t triggering further arrhythmia. Recordings can be shared with the care team during prenatal visits.

Ellie Hartman

October 4, 2025 AT 02:32Take it slow, trust your care team, and prioritize your well‑being.

Alyssa Griffiths

October 9, 2025 AT 08:10Firstly, the risk stratification algorithm mentioned in the article is fundamentally flawed; it fails to account for the nuanced hemodynamic shifts occurring during the second trimester, which are pivotal in AFib pathophysiology!!! Moreover, the omission of genetic predisposition data is a glaring oversight; literature consistently demonstrates a hereditary component that cannot be ignored.

Jason Divinity

October 14, 2025 AT 13:49When evaluating atrial fibrillation in pregnancy, one must adopt a multidimensional perspective that integrates hemodynamics, pharmacology, and obstetric considerations.

First, the cardiovascular system undergoes a 30‑50% increase in blood volume, which inherently predisposes to tachyarrhythmias.

Second, the hormonal milieu, particularly elevated estrogen and progesterone, modulates autonomic tone and can unmask latent conduction abnormalities.

Third, the safety profile of anti‑arrhythmic agents shifts dramatically; drugs such as flecainide, while effective in non‑pregnant adults, lack robust teratogenic data and are generally avoided.

Fourth, beta‑blockers, especially metoprolol, remain the cornerstone of rate control due to their extensive safety record across all trimesters.

Fifth, low‑molecular‑weight heparin is the anticoagulant of choice, given its inability to cross the placenta and predictable pharmacokinetics.

Sixth, vigilant monitoring of anti‑Xa levels is essential because plasma volume expansion can dilute drug concentrations, necessitating dose adjustments.

Seventh, electrical cardioversion after 12 weeks gestation is considered safe and should be pursued when hemodynamic instability persists despite optimal medical therapy.

Eighth, catheter ablation is typically postponed until the postpartum period, unless the arrhythmia proves refractory and life‑threatening.

Ninth, multidisciplinary coordination among cardiology, obstetrics, anesthesiology, and hematology cannot be overstated; each specialty contributes critical insight to deliver optimal maternal‑fetal outcomes.

Tenth, labor planning should incorporate continuous ECG monitoring and a pre‑emptive switch from LMWH to unfractionated heparin within 12 hours of delivery to facilitate rapid reversal.

Eleventh, postpartum follow‑up extending at least six months is advisable to assess for recurrence and to re‑evaluate the need for long‑term rhythm or rate control strategies.

Twelfth, patient education regarding warning signs-such as sudden dyspnea, chest pain, or neurologic deficits-remains paramount.

Thirteenth, breastfeeding compatibility is well‑established for LMWH, allowing mothers to maintain anticoagulation without compromising infant health.

Fourteenth, clinicians should document baseline ECG and echocardiographic parameters to track structural changes over time.

Fifteenth, shared decision‑making empowers patients, ensuring that therapeutic choices align with personal values and risk tolerance.

Finally, the evolving literature underscores that individualized care, rather than a one‑size‑fits‑all algorithm, yields the best outcomes for pregnant patients with atrial fibrillation.

andrew parsons

October 19, 2025 AT 19:28In reviewing the protocol, one observes that the anticoagulation hierarchy is impeccably logical; LMWH precedes UFH, and both unequivocally supersede warfarin and DOACs!!! 📈 Additionally, the recommendation for synchronized cardioversion post‑first trimester aligns with current ESC guidelines, thereby reinforcing best‑practice adherence.

Sarah Arnold

October 25, 2025 AT 01:07🔹 Rate control should be the first line unless the patient is severely symptomatic-metoprolol 25‑100 mg BID is a solid starting point.

🔹 If beta‑blockers cause hypotension, consider diltiazem 80‑120 mg TID, but monitor maternal blood pressure closely.

🔹 LMWH dosing: 1 mg/kg SC q12h, adjust by anti‑Xa levels.

🔹 Remember to switch to UFH 12 h before delivery for rapid reversal.

🔹 Post‑delivery, you can transition back to warfarin if long‑term anticoagulation is needed, keeping lactation considerations in mind.

Rajat Sangroy

October 30, 2025 AT 05:46Listen up-if you’re feeling that racing heart, don’t wait for the next prenatal visit. Call your cardiology team now, get that ECG, and start the beta‑blocker regimen. Time is muscle, and time is baby.

dany prayogo

November 4, 2025 AT 11:25Oh, sure, let’s all pretend that the “standard” risk calculator covers every nuance of a pregnant woman’s physiology-because obviously a one‑size‑fits‑all spreadsheet can capture the complex interplay of hormonal shifts, plasma volume expansion, and the subtle art of patient‑specific decision‑making, right??? In reality, most clinicians just skim the table, ignore the footnotes, and hope for the best, all while the mother‑to‑be silently worries about the very real possibility of placental insufficiency or even a catastrophic thrombo‑embolic event.

Wilda Prima Putri

November 9, 2025 AT 17:03Nice overview, but remember: not every “palpitation” is a heart attack. Keep it chill.

Edd Dan

November 14, 2025 AT 22:42I think the article does a good job, but i think they could add more about diet and exercise during pregnancy. also, the tone could be a bit less medicaly.

Cierra Nakakura

November 20, 2025 AT 04:21Great info! 👍💪 It really helps to see the step‑by‑step plan laid out, especially the parts about switching anticoagulation before labor. Keep the practical tips coming! 😊

Sharif Ahmed

November 25, 2025 AT 10:00One must acknowledge that the discourse presented herein borders on the pedestrian; a truly erudite treatment would delve deeper into the electrophysiological substrates altered by gestational hormone flux, and would juxtapose contemporary ablative innovations against the backdrop of fetal safety thresholds.

Charlie Crabtree

November 30, 2025 AT 15:39Awesome breakdown! 🚀 If you’re pregnant and dealing with AFib, remember you’re not alone-your care team is your squad. Stay positive, follow the plan, and you’ll get through it! 🙌

RaeLyn Boothe

December 5, 2025 AT 21:17Just a heads‑up: make sure you have a backup cardio‑vascular specialist on call when you go into labor. It’s better to be over‑prepared.

Fatima Sami

December 11, 2025 AT 02:56The article is well‑written; however, it should consistently use "LMWH" rather than alternating with "low‑molecular‑weight heparin".

Arjun Santhosh

December 16, 2025 AT 08:35nice work! maybe add a bit mor info on how to manage stress during pregnancy?

Stephanie Jones

December 21, 2025 AT 14:14Isn't it fascinating how the heart's rhythm mirrors the ebb and flow of life's uncertainties, especially when a new life is forming within? The paradox of vulnerability and resilience resides in each heartbeat.

Nathan Hamer

December 26, 2025 AT 19:53⚡️Behold the symphony of cardiology and obstetrics-where every electrical impulse sings a lullaby of hope, and every anticoagulant dose composes a stanza of safety! 🎶✨ Embrace the journey, dear reader, and let knowledge be your guiding star. 🌟