Diabetic Kidney Disease: Why Early Albuminuria Detection and Tight Control Save Kidneys

Feb, 13 2026

Feb, 13 2026

When you have diabetes, your kidneys are quietly at risk - even if you feel fine. The earliest warning sign isn't pain, swelling, or fatigue. It's something most people never hear about: albuminuria. This isn't just a lab result. It's your body shouting that kidney damage has already begun. And here’s the truth: catching it early and controlling it tightly can stop kidney failure before it starts.

What Albuminuria Really Means

Albumin is a protein your kidneys normally keep in your blood. When they start to leak, albumin spills into your urine. That’s albuminuria. It’s not a disease itself - it’s the first red flag of diabetic kidney disease (DKD). For decades, doctors called it "microalbuminuria" when levels were slightly high. But since 2012, guidelines from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) have dropped that term. Why? Because any albumin in urine means damage. There’s no safe middle ground.

The test is simple: a urine sample measures the ratio of albumin to creatinine (UACR). Normal is under 30 mg/g. Moderately increased? 30 to 300 mg/g. Severely increased? Over 300 mg/g. These numbers aren’t arbitrary. They’re based on decades of data from studies like the DCCT and EDIC trials, which tracked over 100,000 people with diabetes. The results were clear: even small increases in albuminuria raise your risk of heart attack, stroke, and needing dialysis.

Here’s what that looks like in real life. A 58-year-old with type 2 diabetes has a UACR of 85 mg/g. Her doctor says, "It’s just a little high. Keep an eye on it." But that number means her risk of dying from heart disease is 73% higher than someone with normal levels. This isn’t a borderline result - it’s a diagnosis.

Why Waiting Is Dangerous

Many people think, "I’ll wait until I feel sick." But DKD doesn’t wait. By the time swelling, fatigue, or high blood pressure show up, your kidneys have already lost 30-50% of their function. And once that’s gone, it’s mostly irreversible.

The progression is predictable. Albuminuria starts. Then, your kidney filter slowly breaks down. Your eGFR (a measure of kidney function) drops. Eventually, you reach end-stage kidney disease - and need dialysis or a transplant. The good news? You can interrupt this chain. The bad news? Most people never even know they’re on it.

Research from the UKPDS study shows that for every 1% drop in HbA1c, your risk of kidney damage drops by 21%. That’s not a small benefit. That’s life-changing. And it’s not just about sugar. High blood pressure? It’s a second hit to your kidneys. When both are out of control, damage accelerates.

Tight Control Isn’t Optional - It’s Your Shield

Tight control means two things: blood sugar and blood pressure. And it’s not about perfection. It’s about consistency.

For blood sugar, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends HbA1c under 7% for most people with diabetes. But if you’re younger, have had diabetes for less than 10 years, and don’t have low blood sugar episodes, aiming for under 6.5% can cut DKD risk even further. The DCCT trial proved this: people who kept HbA1c around 7% cut their risk of microalbuminuria by 39% and proteinuria by 54% compared to those with HbA1c near 9%. And here’s the kicker - those benefits lasted for decades. Even after the trial ended, the group with tight control had far fewer kidney problems 20 years later. That’s "metabolic memory" in action.

For blood pressure, guidelines are mixed. KDIGO says aim for under 120/80 if your UACR is over 300. But the SPRINT trial showed that pushing systolic pressure below 120 reduced albuminuria by 39% - but also raised the risk of acute kidney injury in 1 out of every 47 people. So the ADA recommends under 140/90 for most. The key? Don’t ignore it. If your pressure is 150/95, you’re not just at risk - you’re accelerating damage.

Screening Isn’t Optional - It’s Life-Saving

Every person with type 2 diabetes should get a UACR test at diagnosis. For type 1 diabetes, test after five years. And then? Every year. That’s the ADA’s Class A recommendation - the highest level of evidence. Yet, in real clinics, only 58-65% of patients get tested. Why? EHR systems don’t remind doctors. Patients forget to bring samples. Providers don’t know how urgent it is.

Here’s the reality: if you don’t test, you can’t treat. And if you can’t treat, you can’t prevent.

Some labs use spot checks. Others use overnight collections. But the numbers stay the same: 30-300 mg/g is moderately increased. Over 300 is severe. And because urine albumin can spike temporarily - after exercise, infection, or high blood sugar - you need two out of three abnormal results within 3-6 months to confirm it’s real. Don’t panic over one high number. But don’t ignore it either.

Treatment Has Changed - And It’s More Effective Than Ever

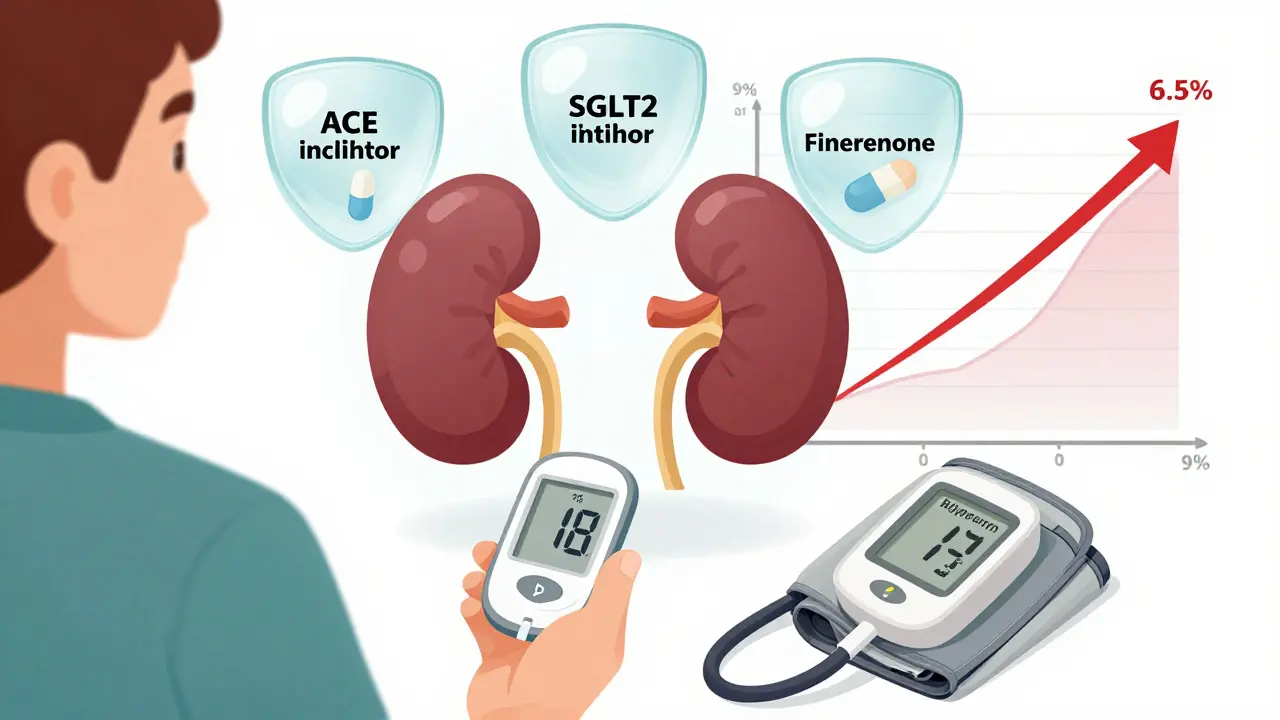

For years, ACE inhibitors or ARBs were the only tools. They helped. But now, we have more.

First-line treatment? Start with an ACE inhibitor or ARB. The IRMA-2 trial showed losartan cut progression from micro- to macroalbuminuria by 53%. And you don’t need high blood pressure to use it. Give it at the maximum approved dose - even if your pressure is normal. It’s protecting your kidneys, not just lowering pressure.

Then add an SGLT2 inhibitor. The 2023 EMPA-KIDNEY trial proved empagliflozin reduced the risk of kidney failure by 28% in patients with UACR over 200 mg/g. It works even if you’re already on an ACE inhibitor. And it doesn’t just protect kidneys - it cuts heart failure and death.

And now? Finerenone. This new drug, a non-steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist, reduces albuminuria by 32% in just four months. In three years, it slows kidney decline by 23%. It’s not a magic bullet - but it’s a powerful addition when you’re already on maximum ACE/ARB therapy.

Here’s the shocking part: only 28.7% of people with DKD get all three of these therapies. Why? Cost. Access. Lack of awareness. In one study, 63% of treatment gaps were tied to socioeconomic factors - not medical ones. That’s not a health issue. That’s a system failure.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to wait for a specialist. Start now.

- Get your UACR tested - if you haven’t had one this year, ask for it.

- If your result is over 30 mg/g, don’t wait. Talk to your doctor about starting an ACE inhibitor or ARB.

- Ask if an SGLT2 inhibitor (like empagliflozin or dapagliflozin) is right for you.

- Keep your HbA1c under 7%. If you’re healthy enough, aim for 6.5%.

- Check your blood pressure at home. If it’s over 140/90, it needs attention.

- Don’t skip urine tests because "it’s inconvenient." One sample can change your future.

And if you’re a provider? Set up EHR alerts. Track UACR like you track HbA1c. Use point-of-care testing. Involve pharmacists. You’re not just managing numbers - you’re preventing dialysis.

The Bigger Picture

Diabetic kidney disease isn’t inevitable. It’s preventable. But only if we act early. Only if we treat tightly. Only if we test regularly.

The data is clear: if every person with diabetes got annual UACR screening, and if everyone with albuminuria got ACE/ARB, SGLT2i, and finerenone when needed, we could prevent 1.2 million new cases of DKD in the U.S. by 2030. That’s 37% fewer people on dialysis. And $14.8 billion saved.

It’s not about hope. It’s about action. Your kidneys are listening. Are you?

What is the normal range for UACR in diabetic patients?

The normal range for urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR) is less than 30 mg/g. Levels between 30 and 300 mg/g indicate moderately increased albuminuria, and over 300 mg/g means severely increased albuminuria - both are signs of kidney damage in diabetes. These thresholds are set by KDIGO and ADA guidelines.

How often should people with diabetes get tested for albuminuria?

Everyone with type 2 diabetes should be tested at diagnosis. For type 1 diabetes, testing starts after five years of disease. After that, annual screening is recommended. If albuminuria is found, testing should be done every 3-6 months until treatment stabilizes it. Quarterly checks are advised after starting medications like ACE inhibitors or SGLT2 inhibitors.

Can tight blood sugar control really prevent kidney damage?

Yes. The DCCT/EDIC studies showed that keeping HbA1c under 7% reduced the risk of developing microalbuminuria by 39% and progression to proteinuria by 54% in type 1 diabetes. In type 2 diabetes, each 1% drop in HbA1c lowers kidney disease risk by 21%. These benefits last for decades - even after blood sugar control is relaxed. Tight control isn’t just helpful - it’s protective.

Why do some doctors still delay treatment until albuminuria is severe?

Many providers aren’t aware that any albuminuria - even moderately increased - signals active kidney damage. Others assume treatment is only needed if blood pressure is high. But guidelines now say: treat early. Start ACE inhibitors or ARBs at maximum dose even if BP is normal. Delaying treatment until macroalbuminuria appears means damage is already advanced.

What are the new drugs for diabetic kidney disease?

Three major drugs are now standard: ACE inhibitors or ARBs (like losartan or lisinopril), SGLT2 inhibitors (like empagliflozin or dapagliflozin), and finerenone. SGLT2 inhibitors reduce kidney failure risk by 28%, and finerenone slows eGFR decline by 23% over three years. These are used alongside each other - not as alternatives. They work through different pathways to protect the kidneys.

Can albuminuria go away?

Yes - and that’s one of the most hopeful parts. Studies show that with tight blood sugar control, blood pressure management, and medications like ACE inhibitors and SGLT2 inhibitors, albuminuria can drop back into the normal range. In fact, reducing UACR by over 30% from baseline is linked to a 48-56% lower risk of kidney failure. Early, consistent treatment doesn’t just slow damage - it can reverse it.

What causes a false high UACR reading?

Several things can temporarily raise albuminuria: intense exercise within 24 hours, fever, infection, heart failure, very high blood sugar (over 300 mg/dL), severe high blood pressure (over 180/110), or menstruation. If one test is high, don’t panic. Retest after these factors are resolved. Always confirm albuminuria with two abnormal results over 3-6 months.

Is it true that only 12% of diabetics meet all three targets: sugar, BP, and cholesterol?

Yes. NHANES data from 2017-2018 showed that only 12.2% of U.S. adults with diabetes achieved optimal control of HbA1c, blood pressure, and LDL cholesterol. This gap is why DKD remains so common. Most people manage one factor - but not all three. True prevention requires addressing all three simultaneously.

Virginia Kimball

February 14, 2026 AT 10:33Mandeep Singh

February 15, 2026 AT 12:17Josiah Demara

February 16, 2026 AT 13:40Kaye Alcaraz

February 17, 2026 AT 01:28Betty Kirby

February 17, 2026 AT 18:30Erica Banatao Darilag

February 19, 2026 AT 06:52Charlotte Dacre

February 21, 2026 AT 03:05Chiruvella Pardha Krishna

February 21, 2026 AT 16:46