Never Use Household Spoons for Children’s Medicine Dosing: Why It’s Dangerous and What to Use Instead

Feb, 9 2026

Feb, 9 2026

Using a kitchen spoon to give your child medicine might seem quick and easy - but it’s one of the most common and dangerous mistakes parents make. Every year, more than 10,000 calls to poison control centers in the U.S. alone are about kids getting the wrong dose of liquid medicine. And in most cases, it’s not because the prescription was wrong. It’s because someone used a spoon from the drawer.

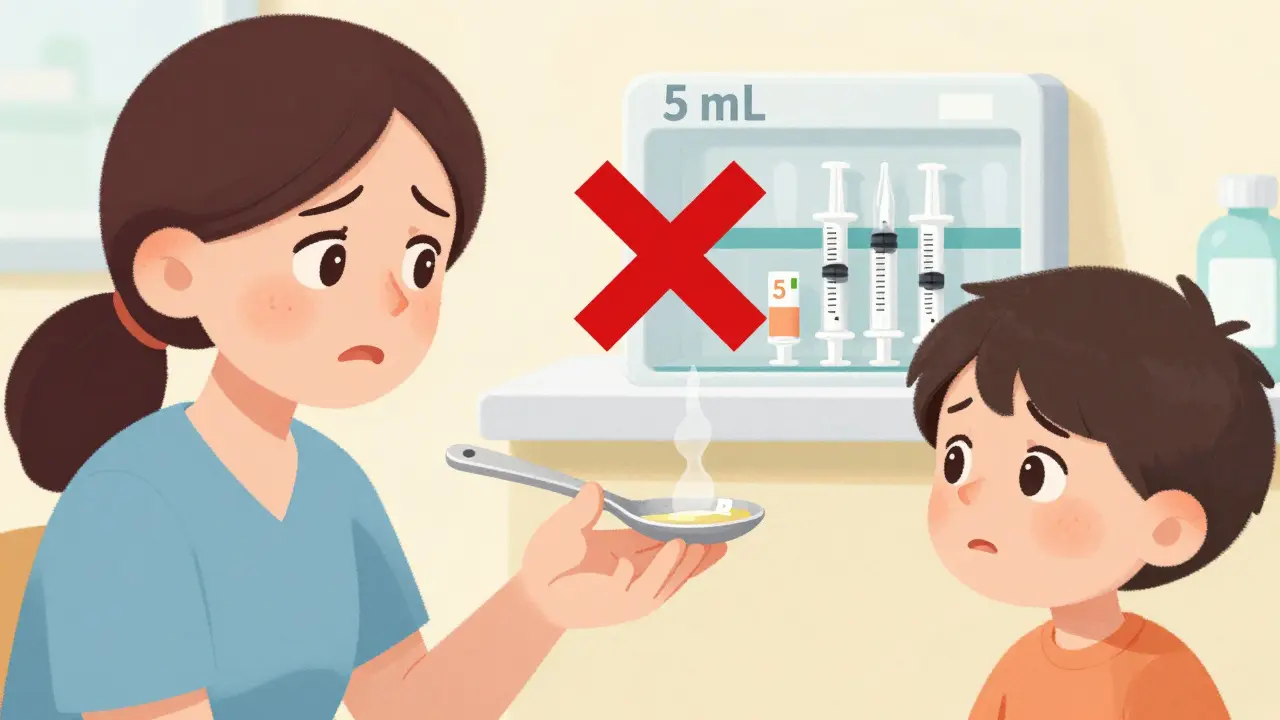

Why Household Spoons Are a Recipe for Trouble

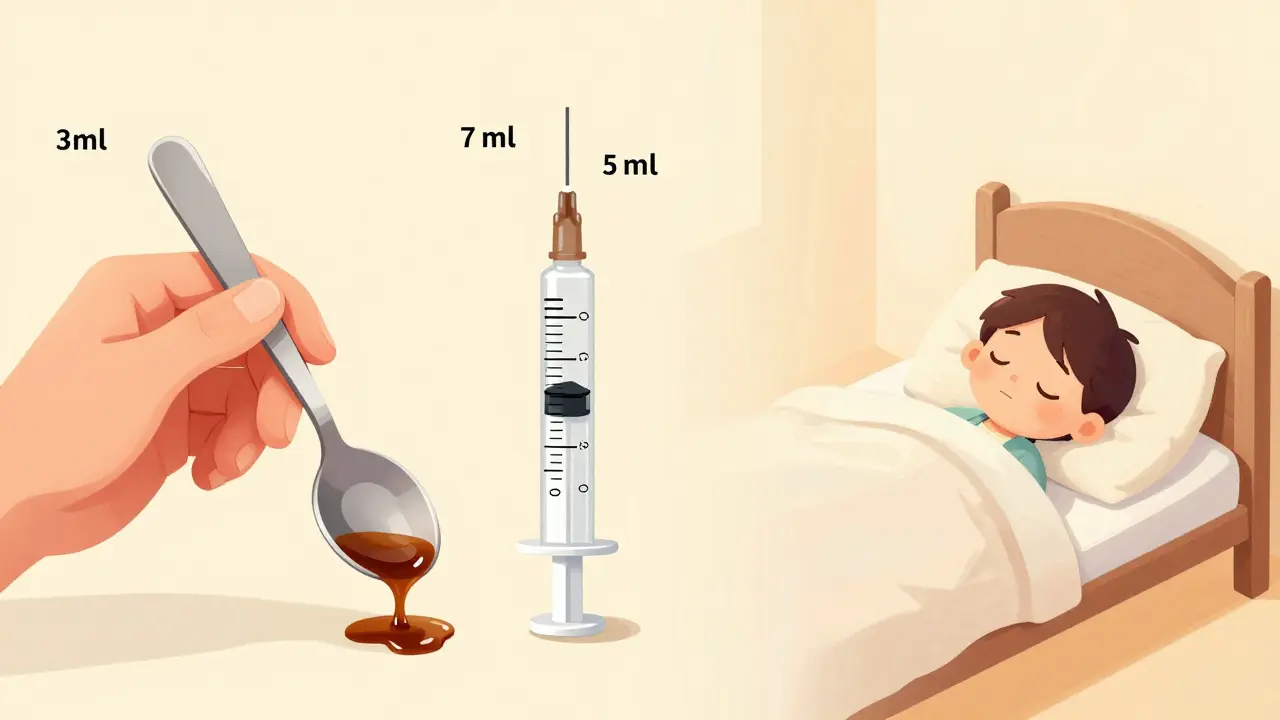

A teaspoon sounds simple. But not all teaspoons are the same. A medical teaspoon is exactly 5 milliliters (mL). That’s the standard used by doctors and pharmacists. But the spoon you use to stir your coffee? It could hold anywhere from 3 mL to 7 mL. That’s a 40% difference. One spoon might give your child too little medicine. Another might give them too much - and too much can be deadly. The CDC calls this the "Spoons are for Soup" problem. Their campaign reminds parents: if it’s not labeled for medicine, it shouldn’t be used for medicine. A tablespoon? That’s three times the dose of a teaspoon. If you think you’re giving 5 mL but you’re using a tablespoon, you’re giving 15 mL - three times the intended dose. For a toddler, that could mean vomiting, drowsiness, breathing trouble, or even hospitalization. A 2014 study in Pediatrics found that nearly 40% of parents made mistakes when measuring liquid medicine with kitchen spoons. Over 41% gave the wrong amount - even when they thought they were doing it right. And the problem isn’t just about confusion. It’s about how labels are written. When a bottle says "give 1 tsp," 33% of parents reached for a kitchen spoon. But when it said "5 mL," less than 10% did. The word "teaspoon" itself is the problem.What You Should Use Instead

The safest tool for giving liquid medicine to a child is an oral syringe. These are small, plastic, needle-free syringes with clear milliliter markings. They’re designed to measure as precisely as 0.1 mL. That’s critical because many pediatric doses aren’t neat numbers. A 3.5 mL dose? A 2.3 mL dose? You can’t measure those with a cup or a spoon. But you can with a syringe. Oral syringes are also easy to use. You draw up the right amount, then gently squirt the medicine between your child’s cheek and gum - not straight to the back of the throat. That reduces choking risk and helps them swallow more easily. Most pharmacies now give these out for free when you pick up liquid medicine. If they don’t, ask. Pharmacists say they’re happy to provide one. Dosing cups are okay - but only if they’re the one that came with the medicine and have milliliter markings. Many cups only show 5 mL, 10 mL, 15 mL. That’s useless for a 7 mL dose. And if you’re using someone else’s cup - like one from a different medicine - you’re risking a mistake.Why Milliliters Are the Only Way to Go

Milliliters (mL) are the universal language of medicine. Not teaspoons. Not tablespoons. Not drops. Just mL. Every liquid medicine for children should be labeled in milliliters - and only milliliters. The FDA and the American Academy of Pediatrics have pushed for this for years. And it’s working. When pharmacies switched from labeling medicine in "tsp" to "mL," dosing errors dropped by 20 percentage points. That’s huge. It means fewer trips to the ER. Fewer hospital stays. Fewer scared parents. Even if the label still says "teaspoon," always convert it. Ask your pharmacist: "How many milliliters is that?" Write it down. Then use the syringe. Don’t rely on memory. Don’t guess. Your child’s body is small. Their system reacts fast. A little too much can cause serious harm. A little too little won’t help them get better.

What to Do When You’re Not Sure

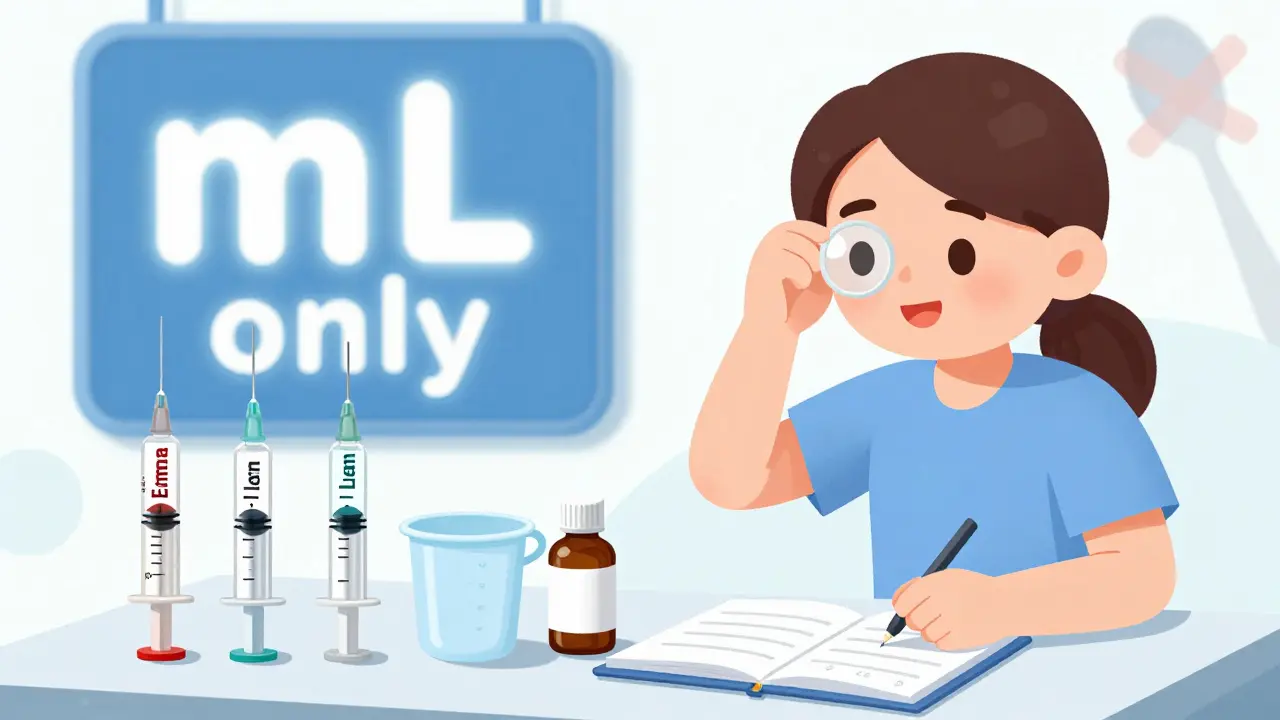

If you open a bottle and there’s no measuring device inside - don’t guess. Don’t use a spoon. Don’t use a regular cup. Call your pharmacist. Ask them to give you a proper syringe or dosing cup. Most will give you one at no cost. If you’re at the doctor’s office, ask for one before you leave. If you’re giving medicine to more than one child, keep their dosing tools separate. Label them with tape or a marker: "Emma’s Syringe," "Liam’s Cup." Never mix them up. Even a small mix-up can lead to a serious mistake. Always measure at eye level. Tilt the syringe or cup so you can see the line clearly. Don’t hold it up high. Don’t look down at it. That’s how you get off by even a few drops. And always double-check the dose. Read the label. Read the syringe. Read it again.The Bigger Picture

This isn’t just about being careful. It’s about changing a habit that’s been around for decades. Many parents grew up using spoons. Their parents did. Their grandparents did. It feels normal. But normal doesn’t mean safe. The data is clear. Using kitchen spoons leads to mistakes. Using milliliter-measured tools leads to accuracy. The American Academy of Pediatrics first warned about this in 1978. Yet today, 75% of Americans still use spoons to give medicine. That’s three out of four families. That’s a public health failure. Pharmacies, hospitals, and clinics are slowly changing. More labels now say "mL" only. More syringes are included with prescriptions. But the biggest change has to come from parents. You have to refuse to use a spoon. You have to ask for the right tool. You have to teach others.

What to Keep in Your Medicine Kit

Make sure you have these on hand for liquid medicines:- At least one oral syringe with clear mL markings (0.1 mL increments)

- A dosing cup that came with the medicine (and only use that one)

- A permanent marker to label each tool by child’s name

- A small notebook to write down doses and times

Final Reminder

Medicine isn’t candy. It’s not something you pour by eye. It’s not something you estimate. For children, precision saves lives. A single teaspoon of error can mean the difference between healing and harm. Use the syringe. Read the mL. Measure at eye level. Ask if you’re unsure. And never - ever - use a household spoon again.Can I use a regular kitchen spoon if I don’t have a measuring tool?

No. Household spoons vary too much in size - some hold as little as 3 mL, others up to 7 mL. A medical teaspoon is exactly 5 mL. Using a kitchen spoon can lead to a 40% overdose or underdose. Always ask your pharmacist for a free oral syringe or dosing cup. Never guess.

Why do medicine labels still say "teaspoon" if it’s dangerous?

Some labels still use "teaspoon" because older printing standards haven’t changed everywhere. But the FDA and American Academy of Pediatrics now require milliliter-only labeling for new products. If you see "tsp" or "teaspoon," ask your pharmacist to convert it to mL. Write it on the bottle. Then use a syringe.

Is a dropper better than a spoon?

A dropper is better than a spoon - but not as good as an oral syringe. Droppers can drip, leak, or be hard to read. They often don’t have clear mL markings. Oral syringes are designed for precision. They’re easier to control, easier to read, and give the most accurate dose - especially for small amounts like 1.5 mL or 3.2 mL.

What if my child spits out the medicine?

Don’t give another full dose right away. Call your pharmacist or doctor. They’ll tell you whether to repeat the dose or wait. Giving extra medicine because your child spit it out is a common cause of overdose. Always check before giving more.

Do pharmacies still give out measuring tools?

Yes. Most pharmacies now include an oral syringe or dosing cup with every liquid pediatric prescription - even if you didn’t ask. If they don’t, ask. They’re required to provide one if you need it. Many also offer them for free to anyone who brings in an empty bottle. Never assume you don’t need one.

Robert Petersen

February 10, 2026 AT 19:02Love this post. Seriously, I used to use spoons too until my kid had a bad reaction. Now I keep three oral syringes in the medicine cabinet-labeled by kid, color-coded, and stored in a ziplock so they don’t get mixed with random crap. Easy. Free. Life-saving.

Pharmacies are way more helpful than people think. Just ask. They’ll hand it to you like it’s a free coffee.

Stop guessing. Start measuring.

Kristin Jarecki

February 11, 2026 AT 09:44While the emphasis on milliliters is absolutely correct, I’d add that the cultural normalization of spoon dosing is deeply tied to generational trust in home remedies. Many parents learned this from their own mothers, who learned it from theirs. It’s not negligence-it’s inherited behavior. The solution isn’t shame. It’s education paired with accessibility. Free syringes at every pharmacy counter, clear labeling on all pediatric prescriptions, and public health campaigns that don’t sound like a lecture.

Change the environment, not the parent.

Alyssa Williams

February 12, 2026 AT 10:46my kid spit out the whole dose last week and i panicked and gave another one lmao

called the pharmacist and she was like ‘oh honey we’ve all been there’

got a syringe for free and now i feel like a responsible adult

Jim Johnson

February 13, 2026 AT 06:09Same. I used to think ‘it’s just a little off’-until my daughter got super drowsy after a cough syrup. Turns out I was using a soup spoon. That was the day I stopped trusting my eyeballs.

Now I measure everything. Even if it’s 2.7 mL. Even if she’s crying. Even if I’m tired.

One drop too much can wreck a whole day. One drop too little? She still gets better.

Just use the damn syringe.

Brad Ralph

February 14, 2026 AT 07:07we live in a world where you can order a drone from your phone but still have to beg for a plastic syringe.

the system is broken.

also i used a teaspoon once.

it was a mistake.

we all make mistakes.

now i have 4 syringes.

one for each kid.

one for emergencies.

one for guests.

one for the dog.

wait no. no dog.

Gloria Ricky

February 15, 2026 AT 02:20i know this sounds basic but if you don’t have a syringe, use the cap on the bottle if it has markings. i learned that the hard way. no spoons. ever. my 2yo almost went to the er because i thought ‘it’s close enough’.

it’s not.

just ask for the syringe. they’ll give it. no judgment.

Jonathan Noe

February 15, 2026 AT 10:50Let’s be real-the reason this is still a problem is because pharmaceutical companies are slow, pharmacies don’t always stock them, and the FDA doesn’t enforce the mL-only rule hard enough. I’ve had bottles labeled ‘1 tsp’ in 2024. That’s not a mistake. That’s negligence.

Also, droppers? Useless. They leak. They drip. They’re calibrated for ‘about 5 mL’ and that’s not good enough for a 4-month-old.

Oral syringes are the gold standard. Period. No exceptions.

Neha Motiwala

February 16, 2026 AT 11:38Do you realize how many people still use spoons because they think ‘it’s just a little bit’? That’s the same logic that lets people drive after one beer. Or skip vaccines because ‘my cousin’s kid is fine’. This isn’t about measuring-it’s about control. People don’t want to be told what to do. They want to feel like they’re doing fine. But your child doesn’t care about your feelings. Your child only cares if the dose is right.

And if you’re still using a spoon? You’re gambling. With your kid’s liver. With their brain. With their life.

Stop being a statistic.

Vamsi Krishna

February 17, 2026 AT 21:06Everyone’s acting like this is a new problem. It’s not. It’s been happening since the 1950s. The real issue? The medical industry profits from repeat ER visits. Think about it. More doses wrong = more prescriptions filled = more sales. They don’t want you to get it right. They want you to keep coming back. Syringes are free? Sure. But they charge $15 for a bottle of children’s Tylenol that should cost $2. The system is rigged.

And now they want you to trust them with a syringe? No thanks.

I use a calibrated pipette from my lab. And I label it ‘DO NOT USE FOR COFFEE’.

Craig Staszak

February 19, 2026 AT 07:46Just got back from the pharmacy and they handed me a syringe without me even asking. Seriously. That’s the kind of service that makes you believe in humanity again.

Also, I started labeling them with masking tape and a Sharpie. ‘Syringe 1: Finn’ ‘Syringe 2: Maya’

It’s weird. But it works.

And yes. I used a spoon once.

Never again.

Stephon Devereux

February 20, 2026 AT 13:01There’s a deeper layer here. The fact that we still use ‘teaspoon’ on labels isn’t just about tradition-it’s about literacy. Many parents don’t read ‘mL’ the same way they read ‘tsp’. One is abstract. One is familiar. The real fix? Education. In schools. In prenatal classes. In the grocery store. We need to teach dosage literacy like we teach traffic signals.

Because this isn’t about spoons.

This is about how we treat knowledge in the home.

And we’re failing.

athmaja biju

February 21, 2026 AT 15:39As an Indian parent, I’ve seen this firsthand. My aunt gave my cousin syrup with a tablespoon because ‘it’s just a little more’. He was hospitalized for 3 days. This isn’t a Western problem. It’s a human problem.

Stop using spoons. Period.

Ask for the syringe. Demand it. If they don’t have it, go to another pharmacy.

Your child doesn’t deserve your laziness.

Brad Ralph

February 23, 2026 AT 07:33just remembered i used a spoon once.

the kid was fine.

so i did it again.

then i cried.

now i have a syringe.

and a shrine.

it’s just a plastic tube.

but it’s my hero.