Phenytoin and Generics: What You Need to Know About Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

Jan, 14 2026

Jan, 14 2026

Why phenytoin is different from other seizure meds

Phenytoin has been used since the 1930s to control seizures, and it still works - but it’s not like other epilepsy drugs. Even small changes in dose can send blood levels soaring into dangerous territory. That’s because phenytoin has non-linear pharmacokinetics. That means if you increase the dose by 25 mg, the blood level might jump by 50% instead of 25%. It doesn’t follow a straight line. This makes dosing tricky even under perfect conditions.

And here’s the real problem: phenytoin’s narrow therapeutic index. The safe and effective range is only 10 to 20 mcg/mL. Go below 10, and seizures might return. Go above 20, and you risk confusion, loss of coordination, or worse. At levels over 40 mcg/mL, people can become unresponsive. Over 100? That’s often fatal.

Most drugs have a wider safety margin. You can miss a dose or take an extra pill without much risk. Not phenytoin. One wrong switch in brand or generic version can tip the balance.

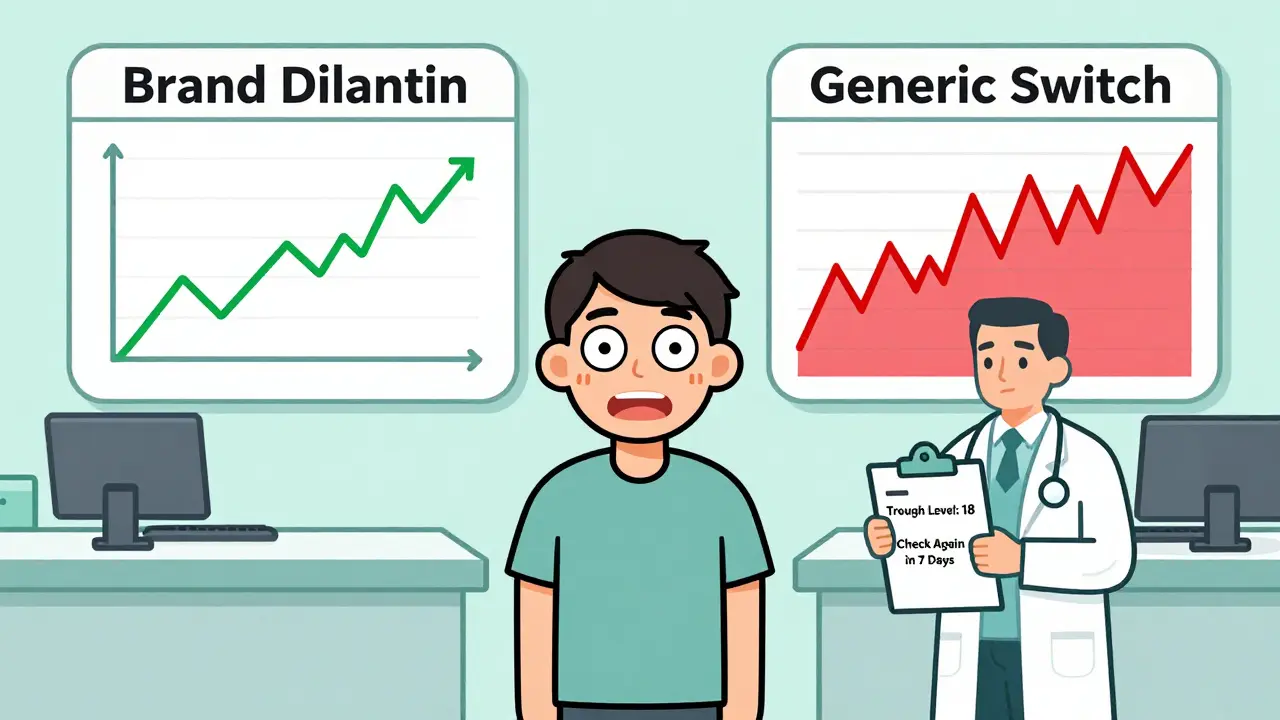

Why generics make phenytoin riskier

All generic drugs must prove they’re bioequivalent to the brand. That means their absorption and blood levels must fall within 80-125% of the original. Sounds fair, right?

But for phenytoin, that 20% variation isn’t harmless. Because of its narrow window and non-linear behavior, a 20% drop in absorption could push a patient from 18 mcg/mL down to 14 - still in range. But a 20% rise? That same patient could jump from 18 to 22 - now in toxic territory.

And it gets worse. Different generic manufacturers use different fillers, binders, and coatings. These excipients can change how quickly the drug dissolves in your gut. One batch might release phenytoin slowly. Another might dump it all at once. The total amount absorbed might look the same on paper, but the timing? That’s what matters for seizure control.

Patients who’ve been stable on Dilantin for years can suddenly start having breakthrough seizures or new side effects after switching to a cheaper generic. It’s not rare. It’s predictable.

When you must check phenytoin levels

Doctors don’t check phenytoin levels for every patient all the time. But when you switch formulations - brand to generic, generic A to generic B - you need a level. Not just one. Two or three.

- Take a trough level right before the switch - this is your baseline.

- Wait 5 to 10 days after the switch, then check again. That’s how long it takes to reach steady state.

- If the patient feels off - dizziness, slurred speech, unsteady gait - check immediately, even if it’s only been 3 days.

Don’t rely on how the patient feels alone. Toxicity can creep in quietly. Nystagmus - involuntary eye movements - is one of the earliest signs. At 20 mcg/mL, you might see mild lateral nystagmus. At 30, it’s obvious. By 40, the person may be confused or drowsy.

And if the patient is on IV phenytoin? A level can be checked 2-4 hours after the dose. Oral? Wait 12-24 hours. Timing matters.

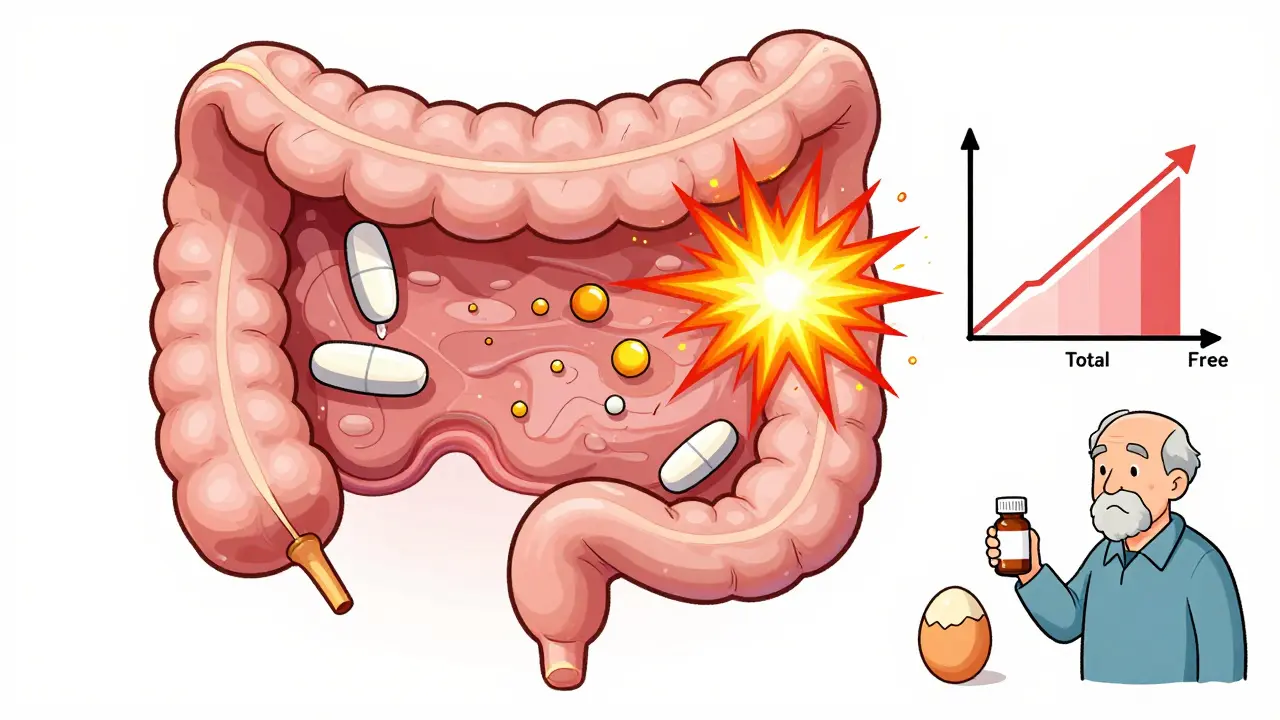

What if the patient has low albumin?

Phenytoin is 90-95% bound to proteins in the blood - mostly albumin. Only the unbound 5-10% is active. That’s why a total level can look normal, but the patient is still toxic.

If someone is malnourished, has liver disease, kidney failure, or is elderly, their albumin might be low. That means more free phenytoin is floating around, even if the total level says it’s safe.

Here’s the fix: check free phenytoin levels. Not the total. The free fraction. If that’s not available, use this formula to estimate:

Corrected phenytoin = Measured level ÷ [(0.9 × Albumin ÷ 42) + 0.1]

But don’t treat the number like gospel. It’s a rough guide. A 65-year-old with low albumin and a corrected level of 18 mcg/mL might still be at risk. Their clinical state - are they stumbling? Slurring words? - matters more than any number.

Other drugs that mess with phenytoin

Phenytoin doesn’t play well with others. It’s metabolized by liver enzymes (CYP2C9 and CYP2C19), and many common drugs interfere.

- Boosts phenytoin levels: Amiodarone, fluconazole, metronidazole, cimetidine, valproate, sulfa drugs.

- Drains phenytoin levels: Rifampin, carbamazepine, alcohol, barbiturates, theophylline.

Switching phenytoin brands while starting a new antibiotic? That’s a recipe for trouble. The antibiotic might raise phenytoin levels - but if you’ve also switched to a generic that absorbs slower, the effect could cancel out. Or multiply. You can’t guess. You have to test.

And don’t forget alcohol. Even moderate drinking can lower phenytoin levels over time, increasing seizure risk. Patients need to know this isn’t just a warning - it’s a safety rule.

Long-term monitoring beyond blood levels

Phenytoin doesn’t just affect your brain. It affects your bones, your gums, your skin, and your blood.

- Gingival hyperplasia: Swollen, overgrown gums - common in up to 50% of long-term users. Regular dental care isn’t optional.

- Bone health: Phenytoin speeds up vitamin D breakdown. That leads to low calcium, low phosphate, and brittle bones. Check vitamin D, calcium, and ALP every 2-5 years.

- Blood counts: It can lower white blood cells. Monitor CBC annually.

- Genetic risk: If the patient is of Han Chinese or Thai descent, test for HLA-B*1502 before starting. This gene increases the risk of a deadly skin reaction called SJS.

These aren’t side effects you can ignore. They build up slowly. A patient might not notice until their toothbrush starts bleeding, or they break a bone from a simple fall.

What to do when switching phenytoin brands

Here’s a simple, step-by-step plan:

- Before switching, get a trough level. Write it down.

- Document the exact product being switched from and to - brand name, generic name, manufacturer, lot number if possible.

- Warn the patient: “You might feel different for a week. Report dizziness, nausea, or new seizures.”

- Check the level again 5-10 days after the switch.

- If the level is outside 10-20 mcg/mL, or the patient feels worse, consider switching back or adjusting the dose.

- Re-check vitamin D, albumin, and CBC in the next 3 months.

Don’t assume generics are interchangeable. They’re not. Not for phenytoin.

What if the patient is stable on a generic?

Some people stay stable on a generic for years. That’s great. But don’t assume they always will be.

Manufacturers change suppliers. Formulations get tweaked. The generic you’re on today might not be the same one next year. If the pharmacy switches your refill without telling you - even if it’s still labeled “phenytoin” - get a level checked.

Ask your pharmacist: “Is this the same manufacturer as last time?” If they don’t know, or say “it’s the same drug,” push back. It’s not. Not for phenytoin.

Bottom line: Don’t treat phenytoin like any other drug

Phenytoin isn’t a drug you can swap like aspirin. It’s a high-risk medication with a tiny safety margin, unpredictable behavior, and a long list of hidden dangers.

Generic versions are cheaper. That’s good. But cost savings shouldn’t come at the cost of seizures or toxicity. Therapeutic drug monitoring isn’t optional here - it’s the only way to stay safe.

If you’re on phenytoin - whether brand or generic - know your level. Know your albumin. Know your other meds. And never, ever switch without checking.

Crystel Ann

January 15, 2026 AT 09:32Amy Ehinger

January 17, 2026 AT 08:55Nat Young

January 17, 2026 AT 21:13Niki Van den Bossche

January 18, 2026 AT 03:32Frank Geurts

January 18, 2026 AT 10:00Nilesh Khedekar

January 20, 2026 AT 02:19Ayush Pareek

January 20, 2026 AT 14:19Jami Reynolds

January 22, 2026 AT 08:34Iona Jane

January 23, 2026 AT 04:39Jaspreet Kaur Chana

January 24, 2026 AT 01:27Haley Graves

January 24, 2026 AT 15:24Diane Hendriks

January 26, 2026 AT 09:08ellen adamina

January 27, 2026 AT 01:20Gloria Montero Puertas

January 28, 2026 AT 14:06RUTH DE OLIVEIRA ALVES

January 29, 2026 AT 13:04