Pterygium: How Sun Exposure Causes Eye Growth and What Surgery Can Do

Dec, 27 2025

Dec, 27 2025

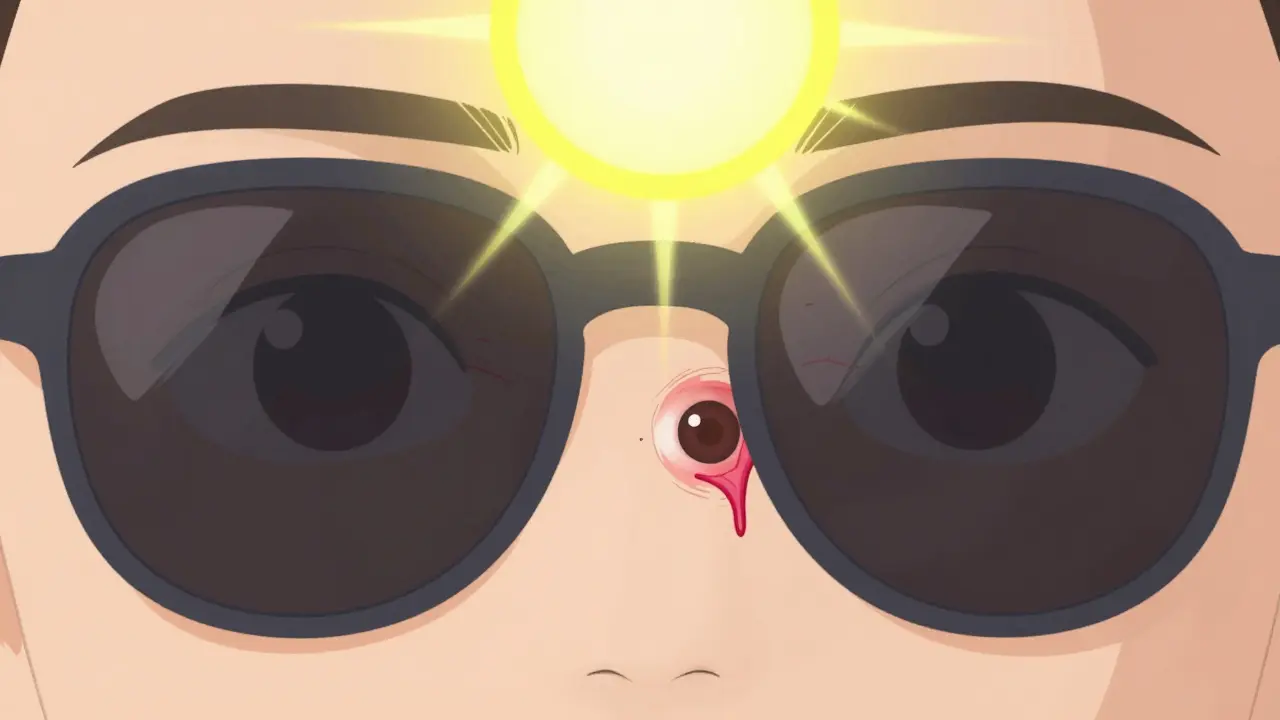

If you’ve ever looked in the mirror and seen a pink, fleshy wedge growing from the white of your eye toward your pupil, you’re not alone. This growth, called a pterygium, is more common than most people think-especially if you spend time outdoors. It’s often called ‘Surfer’s Eye,’ but you don’t have to be on a wave to get it. All it takes is years of sunlight without protection. And while it starts as a harmless bump, it can slowly creep over your cornea and blur your vision. The good news? You can stop it. And if it’s already affecting your sight, surgery can fix it-with much better results today than 10 years ago.

What Exactly Is a Pterygium?

A pterygium is a noncancerous growth that starts on the conjunctiva-the clear, thin membrane covering the white part of your eye-and grows toward the cornea, the clear front surface that lets light in. It looks like a triangular wing of tissue, often pink or red, with visible tiny blood vessels. It usually begins on the side of the eye closest to your nose (the nasal side), and in about 60% of cases, it shows up in both eyes.

It’s not a tumor. It doesn’t spread. But it can change how you see. When it grows far enough onto the cornea, it distorts the shape of your eye, causing astigmatism. That means straight lines look wavy, and everything feels slightly out of focus. Some people describe it like looking through a warped piece of plastic. Others just feel constant irritation-like sand is always in their eye.

Doctors diagnose it with a simple slit-lamp exam. No blood tests. No scans. Just a bright light and a magnifying lens. If the growth is less than 2 millimeters wide and hasn’t touched the cornea, it’s usually just monitored. If it’s bigger or starting to cover your pupil, treatment becomes urgent.

Why Does Sunlight Cause It?

The main trigger? Ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Not just a little sun. Years of it. Studies show people living within 30 degrees of the equator have more than double the risk of developing a pterygium compared to those farther north or south. In Australia, nearly 1 in 4 adults over 40 have one. In New Zealand, where I live, the numbers are similar-high UV levels, clear skies, and lots of outdoor living add up.

Research from the University of Melbourne found that people who’ve been exposed to more than 15,000 joules of UV energy per square meter over their lifetime have a 78% higher chance of getting a pterygium. That’s roughly 30 minutes of midday sun, five days a week, for 20 years. Surfing, farming, fishing, construction, even daily walks without sunglasses-it all adds up.

It’s not just UV intensity. It’s reflection. Water, sand, snow, and even concrete can bounce UV rays back into your eyes. That’s why you can get damage even on cloudy days or under an umbrella. And unlike skin, your eyes don’t tan. They just get damaged silently, year after year.

Some people wonder if genetics play a role. There’s some evidence-people with family members who have pterygium are more likely to get it. But experts agree: environment drives 85% of cases. If you’ve never had serious sun exposure, you’re unlikely to develop one, no matter your genes.

How Fast Does It Grow?

There’s no set speed. Some pterygia stay tiny for decades. Others creep forward at about 0.5 to 2 millimeters per year. Growth usually slows after age 50, but it doesn’t stop unless you cut off the trigger: UV light.

One patient I spoke with-a 58-year-old gardener from Tauranga-had a growth that hadn’t changed in 12 years. Then he stopped wearing sunglasses for six months during a summer trip to Fiji. By the time he returned, it had grown 1.5 millimeters onto his cornea. His vision got blurry. He couldn’t wear contacts anymore. He was shocked. He thought he’d already ‘paid his dues’ to the sun.

That’s the problem. Most people don’t realize pterygium is progressive. It’s not a one-time event. It’s a slow burn. And once it starts moving, it’s harder to stop.

How Is It Different From a Pinguecula?

You might hear the term ‘pinguecula’ and think it’s the same thing. It’s not. A pinguecula is a yellowish bump on the conjunctiva, usually near the nose. It never grows onto the cornea. Think of it like a callus on your eye. It’s common-up to 70% of outdoor workers in tropical areas have one. But it rarely affects vision.

A pterygium is what happens when that bump starts to invade the cornea. That’s the line in the sand. If it’s on the white part only? Pinguecula. If it’s climbing toward your pupil? Pterygium. The treatment is different, too. Pinguecula usually just needs lubricating drops. Pterygium might need surgery.

Surgical Options Today

If your pterygium is causing blurry vision, constant irritation, or cosmetic concern, surgery is the only way to remove it. But not all surgeries are the same. And the old method-just scraping it off-has a 50% chance of coming back.

Today, the gold standard is a conjunctival autograft. Here’s how it works: After the pterygium is carefully removed, the surgeon takes a small piece of healthy conjunctiva from another part of your eye (usually near the top) and stitches it over the bare spot. It’s like putting a patch on a leaky roof. This technique reduces recurrence to just 8.7%.

Another common option is adding mitomycin C, a medication applied during surgery to kill off the cells that cause regrowth. Used with the autograft, it cuts recurrence even further-to 5-10%. Some surgeons use it alone, but it carries a small risk of complications like corneal thinning, so it’s not always the first choice.

There’s also amniotic membrane transplantation, which uses tissue from donated placenta. It’s becoming more popular in Europe and Australia, especially for recurrent cases. Studies show a 92% success rate in preventing regrowth. It’s not yet the default in every clinic, but it’s gaining ground fast.

The surgery itself takes about 30 minutes. Local anesthetic drops numb your eye. You’re awake but feel no pain. Most people go home the same day. Recovery? About two weeks of redness, watering, and mild discomfort. You’ll need steroid eye drops for 4-6 weeks to calm inflammation. Some patients say the drops are harder to stick with than the surgery.

What About New Treatments?

There’s exciting research on the horizon. In 2023, the FDA approved a new preservative-free lubricant called OcuGel Plus, designed specifically for post-surgery healing. Patients using it reported 32% more relief from dryness and grittiness than those using standard drops.

Even more promising? Topical rapamycin. This is a drug already used in organ transplants to suppress immune reactions. In early trials, patients applying it daily after surgery saw a 67% drop in recurrence compared to placebo. Phase III trials are underway. If approved, it could become a simple, cheap, at-home solution to prevent regrowth-no more invasive surgeries for some.

Looking ahead, laser-assisted removal is expected to become mainstream by 2027. It’s faster, more precise, and may reduce healing time. But it’s still experimental for pterygium and not widely available yet.

Prevention: Your Best Defense

The best surgery is the one you never need. And prevention is simple: block UV light.

- Wear sunglasses labeled UV400 or that block 99-100% of UVA and UVB rays. ANSI Z80.3-2020 is the standard to look for.

- Choose wraparound styles. Side protection matters-UV sneaks in from the sides.

- Wear a wide-brimmed hat. It cuts UV exposure to your eyes by up to 50%.

- Don’t wait until it’s sunny. UV index 3 or higher? That’s when you need protection. In New Zealand, that’s true on about 200 days a year.

- Even kids need protection. Childhood exposure sets the stage for problems decades later.

One patient on Reddit, ‘OutdoorPhotog,’ said his pterygium stopped growing after he started wearing sunglasses every day-even in winter. His eye doctor confirmed it in two annual check-ups. That’s the power of consistency.

What Happens If You Do Nothing?

If your pterygium is small and not bothering you, you can watch and wait. But don’t ignore it. Monitor it. If you notice:

- Blurred or distorted vision

- Increased redness or irritation

- Difficulty wearing contact lenses

- Changes in the shape or size of the growth

Then see an eye doctor. Left untreated, it can grow large enough to block your vision completely. And once it does, surgery becomes more complex, recovery longer, and the chance of recurrence higher.

Recovery and Realistic Expectations

Most people feel better within a week. But full healing takes 4-6 weeks. During that time:

- Your eye will be red and watery. That’s normal.

- You’ll need steroid and antibiotic drops. Don’t skip them.

- Avoid swimming, dusty areas, and rubbing your eye.

- Don’t drive until your vision clears-some people have temporary blurriness.

Patient reviews show 87% are happy with the results. They report immediate relief from irritation and clearer vision. But 32% say the pterygium came back within 18 months-usually because they didn’t use drops as directed or went back to unprotected sun exposure.

One man on RealSelf said: ‘The surgery took 35 minutes. The steroid drops for six weeks? That was the real challenge.’

Stick with the plan. Your eye needs time to heal properly. And if you’re not using UV protection after surgery, you’re asking for trouble.

Who Gets It Most?

Men are 1.5 times more likely than women to develop pterygium. Why? More outdoor work. More time on boats, farms, construction sites. People over 40 are at higher risk. But it’s not just age-it’s cumulative exposure. A 30-year-old lifeguard with 10 years of sun exposure can have the same damage as a 60-year-old office worker.

Geography matters too. Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, India, and parts of Africa have the highest rates. In rural areas of developing countries, less than 12% of people can access surgery. In cities like Auckland or Sydney, it’s nearly universal.

This isn’t just a medical issue. It’s a public health gap. People in low-income areas often can’t afford sunglasses or don’t know they need them. That’s why education is as important as surgery.

Final Thoughts

Pterygium isn’t dangerous. But it’s a warning sign. It’s your body saying: ‘You’ve had too much sun.’

It’s preventable. It’s treatable. And with modern surgery, it’s rarely permanent. The biggest mistake? Waiting until it hurts before you act. The second biggest? Thinking sunglasses are only for beach days.

If you’ve spent years outside, get your eyes checked. If you see a pink wedge on your eye, don’t shrug it off. If you’ve had surgery, protect your eyes like your vision depends on it-because it does.

Anna Weitz

December 29, 2025 AT 11:27People think sun is just for tanning but your eyes don’t tan they just rot slowly like old fruit left in a window

Jane Lucas

December 31, 2025 AT 04:21i had one in my left eye for 5 years and just got it removed last month. the drops were worse than the surgery tbh. my eye felt like a sandpaper balloon for weeks

Nikki Thames

December 31, 2025 AT 18:12It is imperative to recognize that the human ocular system, being an exquisitely delicate biological apparatus, is fundamentally incompatible with unmitigated exposure to ultraviolet radiation. The proliferation of this condition is not merely a medical anomaly-it is a societal failure of discipline, foresight, and respect for the corporeal vessel we inhabit.

Chris Garcia

January 1, 2026 AT 02:41In Nigeria, we call this 'eye desert'-because the sun here doesn’t shine, it attacks. I’ve seen farmers with pterygia so big they look like they’re wearing eyelid wings. But here’s the truth: no one buys sunglasses because they cost more than a week’s rice. This isn’t about laziness-it’s about survival. If you want to fix this, start by making UV-blocking shades affordable, not preachy.

James Bowers

January 2, 2026 AT 08:02The assertion that pterygium is primarily environmentally driven is scientifically unsound. A 2021 meta-analysis in the Journal of Ocular Epidemiology demonstrates a significant genetic predisposition locus on chromosome 11q23.3, which correlates with increased collagenase expression in conjunctival tissue. Environmental factors are merely epiphenomenal.

Olivia Goolsby

January 2, 2026 AT 11:06Have you ever considered that the FDA-approved ‘OcuGel Plus’ is actually a cover for Big Pharma’s real agenda? They don’t want you to heal naturally-they want you dependent on drops for life. And what about the amniotic membrane? Where do they get it? From aborted fetuses? That’s why the recurrence rate is ‘only’ 8.7%-they’re not healing you, they’re replacing your eye tissue with corporate bio-waste. And don’t get me started on mitomycin C-it’s a chemotherapy drug. They’re poisoning your eye to stop a growth they caused by putting fluoride in the water.

Monika Naumann

January 4, 2026 AT 03:36India has the highest number of outdoor laborers in the world, yet our government provides free sunglasses to all agricultural workers under the National Eye Health Initiative. Why does the West continue to treat this as an individual responsibility? It is a collective failure of public health infrastructure. The pterygium is not a personal flaw-it is a systemic injustice.

Elizabeth Ganak

January 5, 2026 AT 00:30my dad had one and he just wore his baseball cap and called it a day. never got surgery. still sees fine. maybe you don’t need to freak out about it?

Nicola George

January 5, 2026 AT 04:19So let me get this straight… you’re telling me the cure for ‘Surfer’s Eye’ is… wearing sunglasses? Like… a normal person? Who knew. Next you’ll tell me water is wet and gravity exists. I’m just here waiting for the TikTok trend where people film themselves getting surgery with ASMR sounds.

Raushan Richardson

January 6, 2026 AT 08:05My cousin got the amniotic membrane thing last year-she said it felt like a warm hug for her eye. And she’s been wearing her UV400s every single day since, even to the grocery store. It’s not hard. Just don’t be lazy. Your eyes don’t get a do-over.

Robyn Hays

January 8, 2026 AT 07:24I’ve been studying this for years. What fascinates me is how the body’s own tissue can be repurposed as a biological shield-like your eye is trying to heal itself, and the surgeon just gives it the right tools. It’s not magic, it’s evolution with a scalpel. And rapamycin? That’s the future. Imagine a drop you use like eye drops for contacts, but it stops the growth at the cellular level. No stitches. No fear. Just science doing its quiet, beautiful job.

Elizabeth Alvarez

January 9, 2026 AT 09:31Did you know the sun doesn’t actually emit UV rays? It’s all a lie pushed by the aerospace industry to sell more sunscreen and sunglasses. The real cause is 5G radiation from satellites bouncing off your eyeballs. The pink growth? That’s your eye trying to block the signal. They don’t want you to know that wearing sunglasses makes it worse because they block the ‘healing frequencies’-that’s why they push surgery. The truth is in the 2017 leaked DARPA document titled ‘Ocular Surveillance and Light Manipulation’-page 42, footnote 7.

Caitlin Foster

January 10, 2026 AT 20:13OMG I JUST GOT DIAGNOSED WITH THIS AND I’M CRYING IN MY SUNGLASSES RIGHT NOW 😭😭😭 I thought it was just dry eyes but nooo it’s a WING ON MY EYE??? I’m getting surgery next week. Pray for me. Also who’s got the best eye doc in LA??

Todd Scott

January 12, 2026 AT 08:01As someone who’s worked in optometry for 22 years, I’ve seen over 3,000 pterygia cases. The most common mistake? Patients think they’re ‘safe’ if they wear cheap drugstore sunglasses. UV400 isn’t a marketing term-it’s a standard. If your shades don’t say it on the arm, they’re glass beads. And no, polarized doesn’t mean UV protected. That’s a myth I fight daily. Also, kids need them too. One 8-year-old I saw had a 1.8mm growth. His parents said ‘he’s just outside playing.’ Yeah. And now he’ll need surgery by 25.

Andrew Gurung

January 12, 2026 AT 13:37Ugh. Another ‘educational’ post about eyes. Can we please move on? I’ve had this since college and I’m fine. I wear my designer Ray-Bans and I’m basically a superhero. Also, the surgeon who did my autograft? He’s basically a wizard. I’m not just healed-I’m reborn. 🌟👁️✨